If you logged onto Twitter exactly one year ago, you can probably recall the moment you began to see your feed fill up with gray, yellow, and green boxes. Though it launched in 2021 and gained mainstream popularity in December of that year, Wordle became a sudden cultural phenomenon in early 2022 that was inescapable outside of a muted words list. It was a rare gaming success story, one that could reach a broad audience thanks to its elegant simplicity.

Wordle’s fortune would escalate just as quickly as its user base. In late January 2022, the New York Times announced it had acquired the puzzle game from creator Josh Wardle in an undisclosed, low-seven-figure deal — a left-field move that almost eclipsed Sony’s announcement that it was acquiring Destiny 2 developer Bungie just hours earlier. The move would spark some worry among fans, who feared that a corporate takeover of the most independent game imaginable could steal its soul.

One year later, Wordle hasn’t lost a bit of its charm. The puzzle game is still going strong, and it’s given the New York Times a newfound confidence as it doubles down on its gaming arm. As the publication looks to enter its second year with Wordle, Jonathan Knight, the head of Games at The New York Times, spoke with Digital Trends at CES 2023. Knight reveals what’s been happening behind the scenes over the past 12 months and how NYT Games has found success by resisting the urge to fix what was never broken.

The internet’s game

For The New York Times, the whirlwind Wordle acquisition was a no-brainer. From the jump, the publication felt the game already had the look and feel of one of its own games, down to its modest aesthetic. The deal came together quickly to capitalize on its growing success, but the Games team was just as anxious about ruining a good thing as its players were.

“It took us a bit of time to integrate, and it challenged us,” Knight tells Digital Trends. “Were we really ready for that? Were we ready for that many users? Were we ready to just add another game to our portfolio? Was the platform ready? It stretched a lot of muscles for us that now gives us a different perspective that we could do that again.”

From the beginning, my message to the team was “don’t change anything about this game.”

In order to keep the boat from rocking, the Games team made a decision early on to keep the basics of Wordle unchanged. It would work to augment the experience with outside tools like WordleBot, but Knight recognized that the appeal of the game came from its simplicity.

“Our whole approach from the very beginning was to do no harm to the game,” Knight says. “We recognized that Wordle was an internet treasure. It kind of belonged to the internet. When we bought it, there was a lot of anxiety about what would happen … From the beginning, my message to the team was ‘don’t change anything about this game.’”

While that philosophy would guide Wordle through its first year under The New York Times’ banner, the team wouldn’t close itself off to changes entirely. In fact, Knight notes that the team did consider making some changes and hasn’t ruled out the possibility of doing so down the line to keep it fresh.

“We’d be remiss if we didn’t brainstorm all of the different things we could do to make Wordle more engaging, to retain those users,” Knight says. “That’s not to say that we won’t do those kinds of things in the future. I think we’re definitely over the initial cultural phenomenon and we’re very pleased with the level of audience that’s still on the game. But I think going forward, now that we’ve got the basics covered … I think there’s an opportunity to do more with the game. I wouldn’t ever change the basic nature of the game, but I think there’s more we can do around it.”

Building on elegance

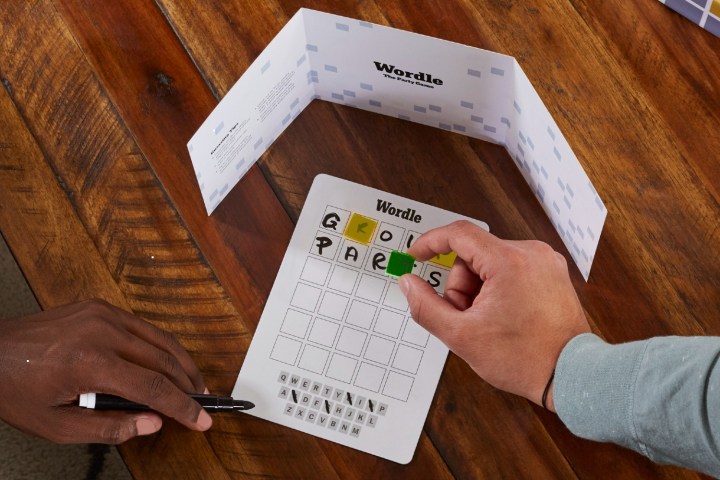

While it may seem like Wordle hasn’t changed much in the last 12 months on its surface, lots has happened behind the scenes. There have been subtle tweaks to the game’s back end, making it easier for players to keep their stats safe. A partnership with Hasbro turned the game into its own franchise, while a recently revealed collaboration with Delta Air Lines will take the game to the open skies.

The most significant (though mostly imperceptible) change came when The New York Times’ Tracy Bennett became Wordle’s official editor, overseeing what was previously a preprogrammed list of words creator Josh Wardle had put together. To an outsider, the idea of an editor monitoring a game that features one five-letter word a day might sound silly. But the New York Times quickly found that it was a necessary step when dealing with a cultural phenomenon.

“It’s important to us to have someone who has that responsibility for what that word is every day,” Knight says. “When we acquired the game, Josh Wardle had preprogrammed several years worth of answers. All those answers were set in your browser. We had no idea it would blow up and take over the world and we’d all be watching Anderson Cooper interview Monica Lewinsky on CNN about Wordle. But that happened!”

Knight’s point was proven last year when the unassuming game ran into its only real controversy. Shortly after a leak revealed the Supreme Court planned to overturn Roe v. Wade, Wordle users ran into an ill-timed solution: fetus. The Games team was aware that the word was in the pipeline days ahead of time, but couldn’t do much about it due to how the word list was programmed.

“That was a moment in time where we had not yet integrated it into our back end,” Knight says. “We weren’t technically able to change the answer on a dime. Fetus had been programmed almost a year earlier on that particular day. We had a programmer who flagged, ‘Hey everybody, in two days the answer is going to be fetus,’ and that was two days after the leaked Roe v. Wade decision had made headlines. We made the editorial decision that it shouldn’t be the answer that day, and if we were fully integrated, we just would have made that change and no one would have ever known.”

The next big thing

The New York Times was quickly able to smooth that out with a few simple decisions (Knight notes that the team hasn’t pulled a word since, but is confident it’ll happen eventually). Since then, Wordle has remained stable, operating in its same daily routine. And while it’s no longer a dominant force on Twitter feeds, its popularity still remains strong. In fact, Wordle was the most searched term on Google in 2022.

My vision for New York Times Games is to be the premier subscription destination for digital puzzles, period.

That success has rubbed off on The New York Times’ other offerings. Knight notes that Spelling Bee in particular has seen growth thanks to Wordle, with the word game landing 77 million “geniuses” in 2022. While Wordle may be a hot topic for players, it’s only one piece of a larger institution that Knight has ambitious plans for.

“My vision for New York Times Games is to be the premier subscription destination for digital puzzles, period,” Knight said. “We have a very big ambition for that and it’s an enormous opportunity. We can reach many more people than we’re reaching now. We can improve our product, our puzzles, our games, the features around the games, the metagame … there’s so much we’re going to be doing to build and deliver a world class, human-made daily puzzle service.”

Can we expect another Wordle-sized phenomenon in 2023? Even Knight admits that it’s unlikely, calling the game a “lightning in a bottle” moment. Even so, Knight says that the game has changed the New York Times’ perception of its gaming brand and put the team on high alert for the next big hit. There may be another unassuming puzzle game creator out there right now who could be the next person to receive a multimillion dollar payout for a good idea.